The lessons from East Asia

By Bill Emmott, co-director GCPPP

There has never been a starker differential between Asian success and western failure than in the management of the health consequences of the pandemic. This has implications for how all countries should prepare for and prevent future crises.

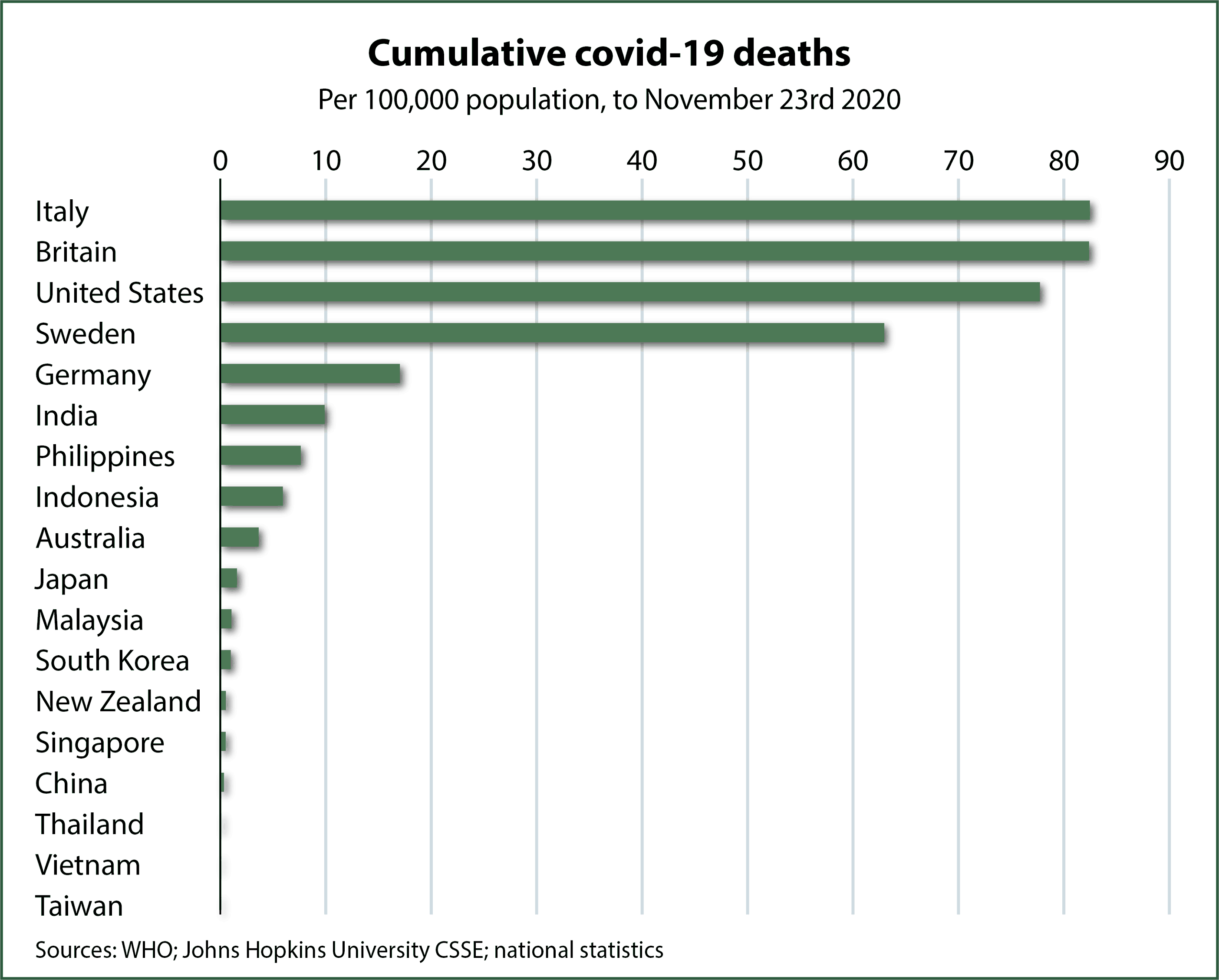

In the early stages of the pandemic, it became common to divide countries and their responses according to their political systems, namely whether they were authoritarian or democratic. This reflected China’s role as the first country to suffer from, and then bring under control, the virus. As 2020 ends, however, it is clear that the real dividing line is not political but geographical: whether countries are democratic or authoritarian, island or continental, Confucian or Buddhist, communitarian or individualistic, every East Asian, South-East Asian or Australasian country has handled Covid-19 better than any European or North American country.

While the line between better and worse health outcomes is not quite hemispheric, it is not far off. As the chart shows, even Asia’s worst performers in terms of health management, such as the Philippines and Indonesia, succeeded better in 2020 in controlling the pandemic’s spread than Europe’s best big countries. In Europe, only Finland and Norway have done as well. In the case of the Philippines as in India, there are reasonable doubts about the quality and accuracy of reports about causes of mortality. But the fact remains: in 2020, you were much likelier to die of covid-19 if you were European or American than if you were Asian.

It is important and urgent that independent, comprehensive, inter-disciplinary research should now be conducted on why this has been the case. For the time being, understanding of the sources of this outperformance remains largely anecdotal and not sufficiently pan-regional, making it vulnerable to political exploitation and distortion. If all countries are to prepare better for future biological threats than for Covid-19, proper research that goes beyond anecdote and cultural preconceptions will be vital.

The elements that need to be explored include:

- The extent to which prior experiences of SARS, MERS, Avian flu and other diseases in many Asian countries left a legacy of greater preparedness in health systems and greater receptiveness in publics to anti-transmission messaging.

- The extent to which public health systems in Asia benefited from existing structures geared to intervening to control outbreaks of infectious diseases such as tuberculosis, cholera, typhoid, HIV-AIDS and others, including extensive community-based public health nurses. Japan, for example, had in 2014 a total of 48,452 employed public health nurses (PHNs) of which 7,266 were located in 460 public health centres, and PHNs were widely used during 2020 for contact tracing. Although definitions of nursing categories vary, a useful comparison is with England in that same year, when according to a government study there were 350-750 public health nurses and 11,000 health visitors. England’s population is roughly 50% as big as Japan’s.

- The role played by measures to protect care homes and other facilities for the elderly, especially in those countries (Japan and South Korea notably) with a high proportion of over-65s in the population.

- The role played by rapid and comprehensive decisions to close borders to international travel.

- The role played by public health communications and how they varied across the region.

- The role, if any, played by genetic differences and past programmes of anti-tuberculosis (BCG) vaccination.

Only on the basis of such research will it be possible to debate the role in this pandemic of social behaviour, states and health systems, and how to prepare better for future risks.

Many commentators are already also wondering what Asia’s 2020 success might imply for public policy, geopolitics and the international system after the pandemic. On the face of it, if future historians seek to pick a date for when ‘the Asian century’ began they might be tempted to choose 2020, just as the publisher Henry Luce famously dated ‘the American century’ from 1941.

That historical comparison provides a first clue as to why such a judgement may be premature, or at least to how it raises further questions. Luce’s America was a single superpower, emerging to claim and define its era. The Asian century, as displayed by Asian success in dealing with the pandemic, is about a whole continent, consisting of a wide range of countries. In particular, it is not simply about China, successful though that superpower has been in coping with the pandemic after its initial failure and lack of transparency. The fact that other Asian countries have been equally successful without Chinese assistance has put clear limits on the gains either to prestige or to notions of systemic superiority that might otherwise have accrued to China.

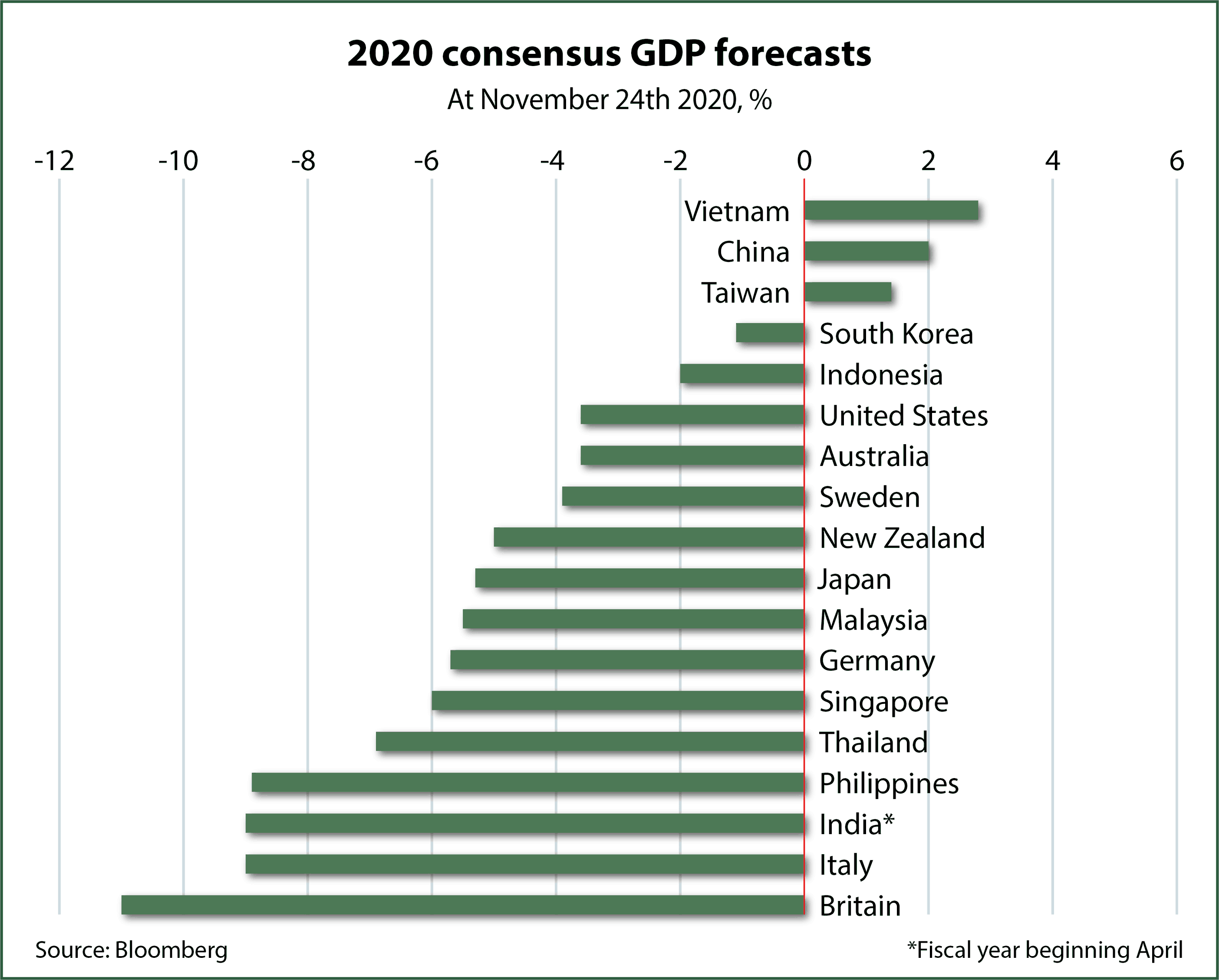

The second clue to why judgement should not be jumped to lies in economics. During the pandemic crises’ first year, Asian superiority in economic outcomes has been a lot less clear than that of health. As the second chart shows, Vietnam, China and Taiwan have all beaten the rest of the world to a resumption of economic growth. But the United States has not fared too badly despite a poor record on health: its forecast outturn for 2020 of a 3.6% fall in GDP is better than all European economies but also better than Japan, Malaysia, Singapore, Thailand, the Philippines and others in Asia. This is in part thanks to inter-connectedness: many Asian economies are more exposed to trade than is the United States. Bans on travel will also have hurt those economies for which tourism provides a considerable income.

Although China’s health and economic performances have both been better than that of the West during 2020, as stated earlier it has not found, or even really sought, political or diplomatic advantage from this. If anything, its “wolf warrior diplomacy” has become more aggressive, both towards near neighbours and further ones such as Australia, suggesting that it is not seeking to build an Asian network of friends and supporters. A key test in 2021 may be China’s approach to demands for international debt restructurings, especially any connected with its own loans related to its ‘belt and road’ initiative.

Yet there will be tests aplenty for the United States and the West, too, including not only debt and international finance but also social stresses and potential disorder. It may be too soon to make a call on a switch of leadership to Asia. But it is not too soon to learn lessons from Asian health success.

GCPPP Newsletter

We now publish a weekly newsletter to inform friends and supporters of the Global Commission’s progress and to provide updates when new content is published. Please sign up here:

Fateme Alaie, Unsplash

Fateme Alaie, Unsplash