The European Union’s vaccine-acquisition strategy

Analysis

By Francois Heisbourg, Commissioner June 23rd, 2021

Reproduced with kind permission of the International Institute for Strategic Studies, who published this as a Strategic Comment

When COVID-19 struck north Italy in late February and early March 2020, the European Union did not organise immediate assistance, with its officials arguing that they had neither the means nor the mandate to do so. As Italy’s plight deepened – with nearly 14,000 deaths by April in the province of Lombardy alone, with roughly ten million inhabitants – its calls were initially answered by China, Cuba and Russia. These countries sought to maximise press and social-media attention for these efforts in a phenomenon that came to be known as ‘mask diplomacy’ even though, over time, EU member states including Austria, France and Germany came to provide far more aid and assistance.

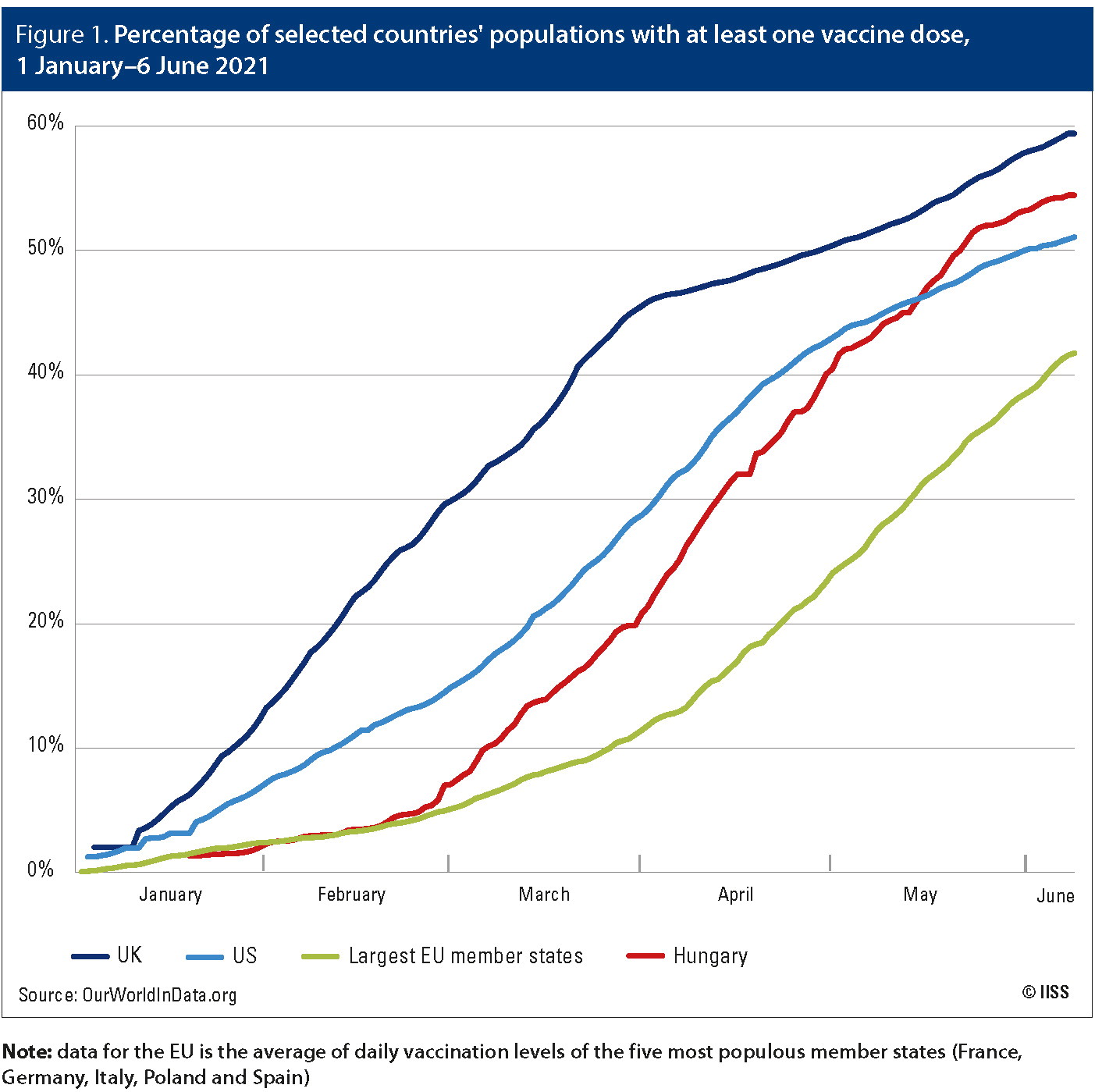

Beginning in June 2020, the EU moved to assume broad new powers and responsibilities for acquiring and distributing vaccines to its member states. However, once pharmaceutical companies began distributing doses in December 2020 and January 2021, the EU fell immediately behind the United Kingdom and United States in the number administered, facing shortages while at the same time allowing a substantial share of the vaccines it did receive to be exported elsewhere. While this gap began to narrow in late spring, the EU’s reputation has been battered as the slow launch of its vaccination campaign has caused deaths that could have been avoided and imposed further economic costs on member states already struggling to recover from successive waves of the pandemic.

The EU’s initially limited role

In late January and February 2020, when the first cases of COVID-19 were detected in Europe and health authorities began taking action to contain the spread of the disease, it was not yet clear that major decisions about the crisis would come to be handled by the EU rather than by national governments. The EU had limited competencies regarding health policy. The budget of the European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control, an EU agency created in 2004, was 100 times smaller than that of its US counterpart, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (US$73m versus US$8 billion, respectively, in 2020).

The European Medicines Agency (EMA), created in 1995, authorises the distribution of pharmaceuticals much like the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA), but it performs this role in addition to (not in place of) national-level bodies that do the same and have the last word on the subject. In 2014, the European Commission (EC) approved a Joint Procurement Agreement to acquire medical countermeasures to be used in the event of a pandemic, but no such stockpile had been set up before COVID-19 emerged.

The EU’s most substantial contribution to the pandemic response in these early weeks was the EC paying for the transportation of personal protective equipment (PPE) and emergency medical supplies to Wuhan, China, where the virus first infected large numbers of people. Several member states, including Estonia, France, Germany, Italy and Latvia, provided this aid, which China accepted on the understanding that it would not be widely publicised.

New EU competencies

The European Council took action on 26 March 2020 when it called on the EC to procure and distribute PPE, ventilators and testing supplies using the Joint Procurement Agreement, with the latter spending roughly US$464m on these efforts in the subsequent 12 weeks. The UK, still in its Brexit transition period, was notified that it could partake in joint procurement but it did not do so, either by choice or because – as some UK officials claimed – the invitation to participate was sent to an outdated email address.

Figure 1. Percentage of selected countries’ populations with at least one vaccine dose, 1 January–6 June 2021

Note: data for the EU is the average of daily vaccination levels of the five most populous member states (France, Germany, Italy, Poland and Spain)

The EU played little role in discussions about vaccine development and procurement until late June 2020. Vaccine research was initially funded and overseen by pharmaceutical companies and national governments. Pharmaceutical researchers at the Institut Pasteur and Sanofi in France and CureVac in Germany had promising vaccine candidates under development. Many member states expressed interest in buying the vaccine that might emerge from the collaboration between the Jenner Institute at the University of Oxford and the British–Swedish company AstraZeneca. On 13 June, France, Germany, Italy and the Netherlands – calling themselves the Inclusive Vaccine Alliance – struck a tentative deal to purchase vaccine doses from the Oxford–AstraZeneca group. Many other EU member states, fearing they might be deprived of timely access to effective vaccines, quickly pointed out the non-inclusive nature of this agreement.

The EU seemed to have concluded by this point that it could play a critical role in the crisis – in part making up for its slow start – as the centralised negotiator for vaccine procurement, with the potential for all member states to receive vaccines more quickly, cheaply and equitably as a result. On 17 June, EC President Ursula von der Leyen and health commissioner Stella Kyriakides released a ‘European strategy to accelerate the development, manufacturing and deployment of vaccines against COVID-19’, offering to make down payments on advance vaccine purchases that would be funded from a US$3.3bn Emergency Support Instrument. Member states did not object. The EC then took responsibility for negotiating the Oxford– AstraZeneca contract, initially agreed by the Inclusive Vaccine Alliance, and for negotiating with other pharmaceutical companies including the Pfizer–BioNTech group, Moderna, Johnson & Johnson, CureVac, Novavax and Sanofi. Three of these announced that their vaccines were effective and ready for release by the end of 2020, with the EMA providing conditional authorisation to distribute vaccines in the EU to Pfizer–BioNTech on 21 December, Moderna on 6 January 2021 and Oxford– AstraZeneca on 29 January, followed by Johnson & Johnson on 11 March.

The EC’s work negotiating contracts proceeded at pace, with the EU signing an agreement to purchase 300–400m doses of the Oxford–AstraZeneca vaccine on 27 August, a day before the UK’s agreement to purchase 100m doses. The EC finalised several other advance-purchase agreements in the remainder of 2020, and by February 2021 it had secured access to 1.7bn prospective doses. On paper, this may have seemed like it would be more than enough for the EU to vaccinate its population of 446m, to keep a reserve, and to offer doses to rich countries such as Canada and Japan and to the COVAX initiative, established by the World Health Organization and the Gavi Vaccine Alliance to provide accelerated vaccine access to 20% of the population of every country in the world. The ability to send doses onwards became even more important after the decisions by the UK and US governments to prohibit the export of vaccines produced domestically.

The EU, apparently considering its position to be secure, did not create a screening mechanism that would allow it to slow or prevent vaccine exports if its own member states were facing shortages. Indeed, in the summer of 2020, EU policymakers probably did not anticipate how important the timing of vaccine deliveries would become. At the time, there was a significant reduction in the number of COVID-19 cases across the bloc – with just over 13,000 deaths between 1 June and 31 August, compared with ten times that number during the previous three-month period – even as the disease remained widespread in the US and in Latin America.

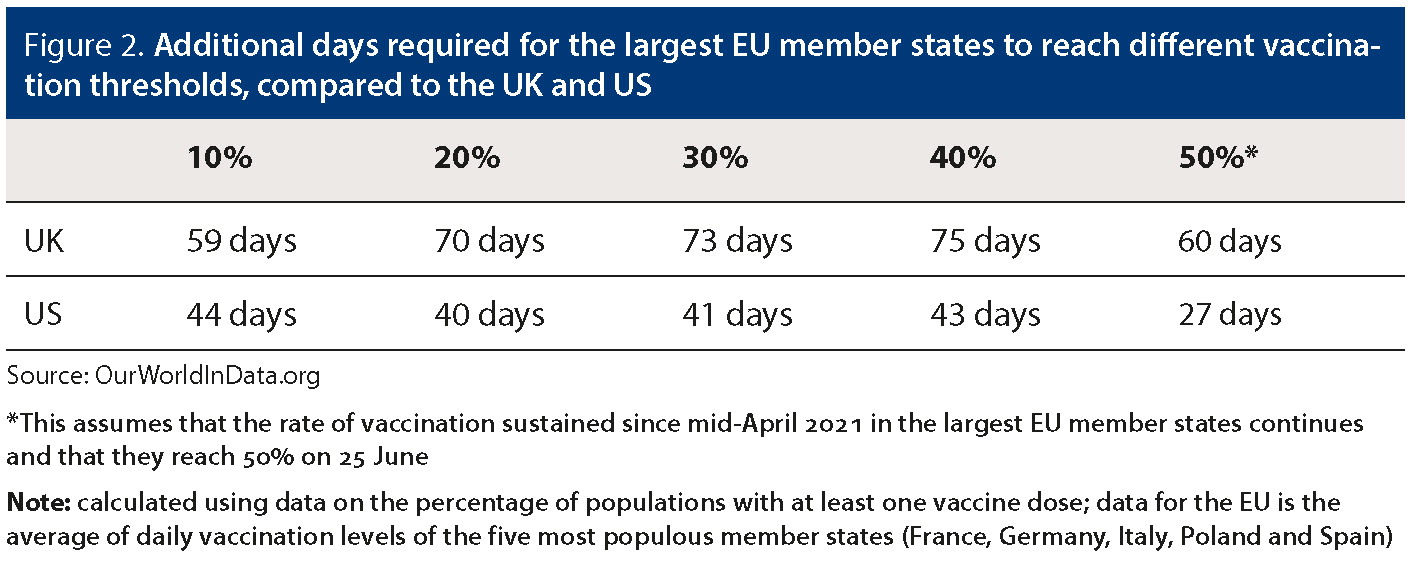

Figure 2. Additional days required for the largest EU member states to reach different vaccination thresholds, compared to the UK and US

Source: OurWorldInData.org

*This assumes that the rate of vaccination sustained since mid-April 2021 in the largest EU member states continues and that they reach 50% on 25 June

Note: calculated using data on the percentage of populations with at least one vaccine dose; data for the EU is the average of daily vaccination levels of the five most populous member states (France, Germany, Italy, Poland and Spain)

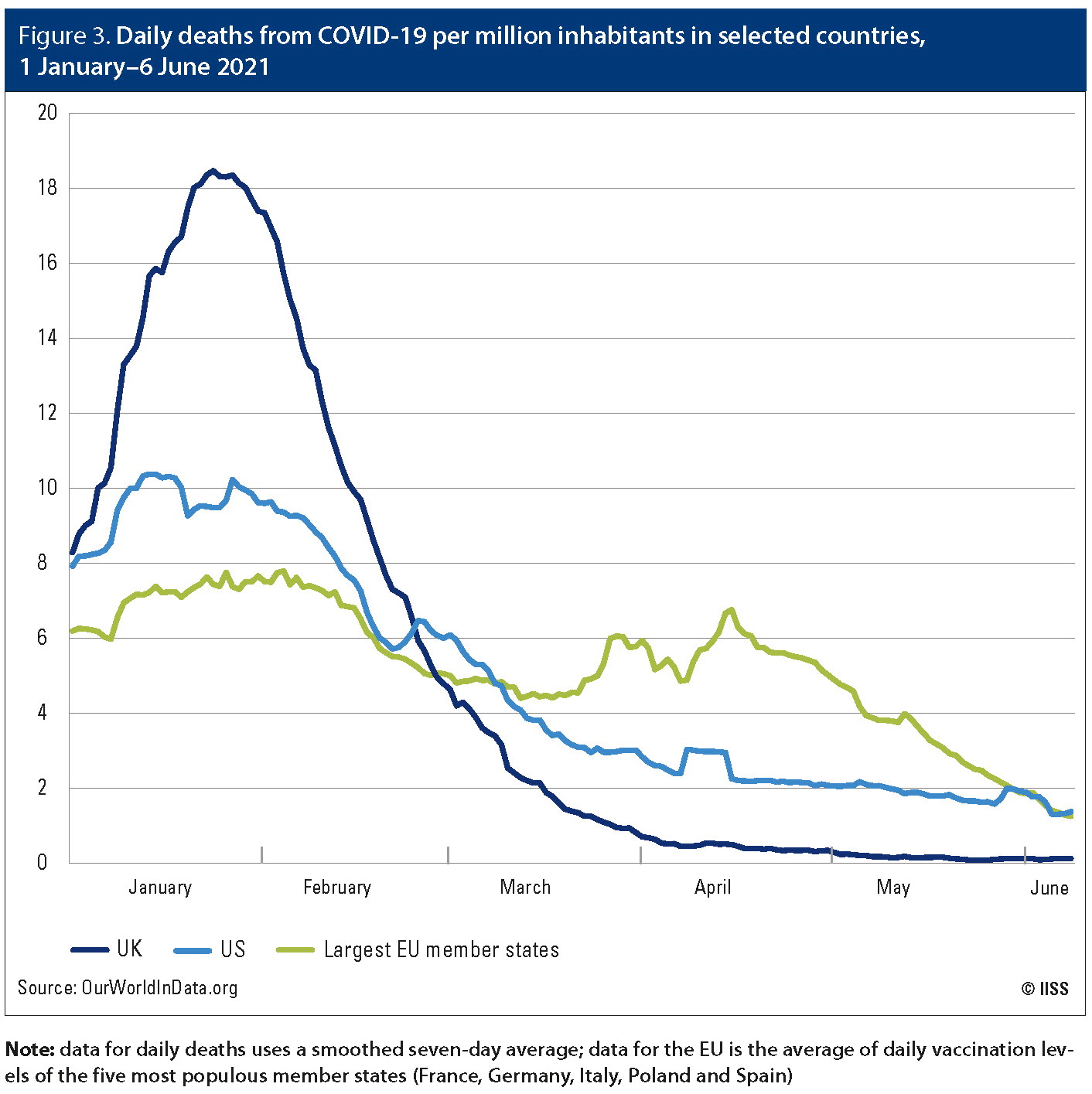

Figure 3. Daily deaths from COVID-19 per million inhabitants in selected countries, 1 January–6 June 2021

Note: data for daily deaths uses a smoothed seven-day average; data for the EU is the average of daily vaccination levels of the five most populous member states (France, Germany, Italy, Poland and Spain)

The late, slow and contentious roll-out

The first vaccine doses (produced by Pfizer–BioNTech) were administered on 8 December 2020 in the UK, on 14 December in the US and on 27 December across the EU. The initial delay in the EU was partly attributable to its slower regulatory process and partly to the fact that Pfizer–BioNTech submitted its approval application to the EMA on 30 November, ten days after its application to the FDA. The UK medicines regulator was the fastest to approve the vaccine (on 2 December), with the US and EU agencies conducting 21-day reviews ending in approvals on 11 December and 21 December, respectively. In the EU, national health agencies had to conduct their own reviews, which added several days to the process.

The EU fell much further behind in early 2021, principally because of a combination of vaccine shortages and the fact that it exported a substantial share of the vaccines it did receive. It became clear by the end of 2020 that the EU would not receive doses from CureVac, Johnson & Johnson or Sanofi in time for the first wave of vaccinations. This meant that the EU had to rely principally on its agreements with Pfizer–BioNTech, which experienced production problems at its manufacturing facility in Belgium, and especially Oxford–AstraZeneca, which delivered vaccines more slowly than expected.

By 1 March 2021, the EU had distributed 7.9 doses per 100 residents, versus 31.9 in the UK and 23.2 in the US. The EU did not begin vaccinating at the same populationadjusted rate as the US until the end of April. By then, the EU had fallen 40 days behind the US and more than 70 days behind the UK in terms of the share of the population having received at least one vaccine dose. The EU closed some of this gap during May, but the lost time – during the deadliest phase of the pandemic in some places – was costly in both human and economic terms.

Just as residents of EU member states were watching those in the UK and US receive vaccines – including those at progressively younger ages – it remained difficult for even the most vulnerable Europeans to receive their first dose. At the same time, a large share of vaccines being produced in the EU were being exported. In the first four months after European production of vaccines began, the number of doses exported exceeded the number distributed domestically (173m versus 133m, respectively). The largest recipients were Japan, Canada and Mexico, in descending order. The UK received 16.2m doses from the EU. It was not until 24 March that the EU created a mechanism allowing doses to be withheld from export, with Italy blocking a shipment meant for Australia.

The shortcomings of the EU’s vaccine strategy led some countries to look elsewhere for help. Hungary ordered vaccines from China’s Sinopharm and Russia’s Gamaleya institute (receiving 3.3m and 2m doses, respectively) in addition to its full share from the EU plan. By 10 May, it had given at least one dose to 45% of its residents, versus the EU average of 28.4%. However, because the third wave of the disease in March and April – just as the vaccination campaign was accelerating – was so severe, the country now has the second-highest death rate of any country in the world (3,084 deaths per million inhabitants as of 3 June). Italy, Slovakia, Slovenia and even Germany (particularly some of its Länder, such as Bavaria and Saxony) also considered turning to Russia, especially after an article published in British medical journal the Lancet in February 2021 suggested that its Sputnik V vaccine is safe and highly effective. However, the vaccine has not yet been approved by the EMA, and Russia has faced production constraints that have created a domestic and export shortage.

Relations between the EU and Oxford– AstraZeneca – and by extension the UK– have been particularly acrimonious. The drug maker failed to deliver doses according to the timetable agreed, while a rare side effect of its vaccine involving blood clots caused widespread concern throughout the EU, leading several member states either to suspend use of the vaccine entirely (such as in Austria, Denmark, Iceland and Norway) or to limit its use to specific age groups. These problems were made worse by EU suspicions that the UK was getting more than its fair share. EC President von der Leyen suggested that she was effectively considering a vaccine embargo towards the UK, while the UK suggested it could halt deliveries to the EU of a key ingredient for vaccine production. The triumphant mood in some quarters of the British press and political class, where many argued that the UK’s successful vaccine roll-out could only have happened because of Brexit, worsened the mood in Brussels. By May, the EU was threatening legal action against Oxford–AstraZeneca over its slow delivery, and at the time of writing it has not placed further orders with the company.

Outlook

In the 50 days from 12 March to 30 April, there were over 59,000 more deaths from COVID-19 in the EU than in the US (adjusted for population). There were over 13,000 more deaths in France alone during a comparable period (the 60 days from 2 March to 30 April) than in the UK. These stark figures cannot be attributed solely to differences in vaccine policies; variants of the virus affected countries unevenly and there were significant differences in national policies regarding lockdowns and travel, which confound such comparisons. However, in time, social scientists will be able to develop credible estimates of the lives lost that can be attributed to the initial delay in the EU’s vaccine campaign, and the figures are likely to be sobering.

In economic terms, the fast pace of vaccination in the UK and US has allowed governments there to lift COVID-19 restrictions earlier than has been the case in the largest EU countries. For example, pubs in the UK resumed outdoor table service on 12 April, while outdoor dining in France did not resume until 19 May. In the first quarter of 2021, preliminary data suggests that the eurozone remained in recession at an annualised GDP growth rate of -2.5% while the US enjoyed 6.5% growth. Here, too, more research is needed to weigh the effects of various factors including differences in vaccination campaigns.

In political terms, the failures of the EU’s early vaccination efforts have undermined its goal of expanding its federal powers over member states. Defenders of the June 2020 decision to entrust the EC with responsibilities for acquiring vaccines argue that things would have been even worse if vaccine nationalism had prevailed. However, the counterfactual nature of this argument gives it little purchase. Non-EU countries such as Iceland, Norway and Serbia have more residents vaccinated than the EU average and do not appear to have suffered from following their own strategies. It seems all but inevitable that this episode will be remembered as a historical policy failure for the EU, yet it will still probably take a hard political push, notably by France and Germany, to force the EC to engage in an honest lessons-learned exercise. This may be one of the only steps it could take to mitigate some of the political fallout from this failure.

Photo by Mika Baumeister on Unsplash

GCPPP Newsletter

We now publish a weekly newsletter to inform friends and supporters of the Global Commission’s progress and to provide updates when new content is published. Please sign up here:

visuals, Unsplash

visuals, Unsplash